Bald Eagle Recovery in Pennsylvania

Today, the bald eagle population in Pennsylvania has rebounded significantly, with numerous nesting pairs spread across the state. The successful reintroduction and recovery of bald eagles in Pennsylvania is a testament to the effectiveness of dedicated conservation efforts and collaboration among various organizations and stakeholders.

This, however, was not always the case. The bald eagle population in Pennsylvania began to decline significantly in the mid-20th century. By the 1950s and 1960s, the combination of habitat loss, hunting, and the widespread use of the pesticide DDT had severely impacted the population. DDT, in particular, caused eggshell thinning, which led to decreased reproductive success. By 1980, only three nesting pairs of bald eagles remained in the state, all located in Crawford County. This dramatic decline prompted concerted conservation efforts to protect and eventually reintroduce bald eagles to Pennsylvania.

DDT being sprayed on crops in the 1950’s DDT being sprayed on crops in the 1950’s |

The use of DDT

Paul Hermann Müller was a Swiss chemist who is best known for his discovery of the insecticidal properties of DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane). After extensive research and testing of various compounds, Müller discovered that DDT was highly effective at killing a wide range of insects. Müller received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1948 for this discovery.

The impact of Müller’s discovery was immediate and far-reaching. During World War II, DDT was used to control the spread of diseases such as typhus and malaria among troops and civilian populations. Its effectiveness in reducing insect-borne diseases saved countless lives and demonstrated the critical importance of chemical insecticides in public health.

After World War II, DDT was widely used in the United States due to its effectiveness as an insecticide for both agricultural and public health purposes. In agriculture, DDT helped protect crops from a variety of insect pests, significantly boosting food production and reducing crop losses. Its broad-spectrum efficacy and relatively low cost made it a popular and seemingly indispensable tool during this period, contributing to increased agricultural yields and significant public health improvements.

Rachel Carson Rachel Carson |

Rachel Carson

Despite the initial success and widespread use of DDT, concerns about its environmental and health impacts began to surface in the 1960’s. Rachel Carson, a marine biologist, conservationist, and Pittsburgh native, played a pivotal role in bringing attention to the environmental impact of DDT through her landmark book, “Silent Spring,” published in 1962. Her work was instrumental in uncovering the detrimental effects of pesticides, particularly DDT, on wildlife, including the thinning of eggshells in raptor species such as bald eagles and peregrine falcons.

One key piece of evidence Carson examined was the correlation between DDT exposure and declining bird populations. She reviewed studies that documented how DDT, once ingested by insects, moved up the food chain to birds.

“Silent Spring” sparked a nationwide environmental movement and led to increased public awareness including the banning of DDT in the United States in 1972.

Reintroduction Program

The Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940 and the banning of DDT in 1972 were crucial steps in providing legal protection and addressing one of the major threats to the eagle population. In the early 1980s, the Pennsylvania Game Commission, in collaboration with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other organizations, developed a reintroduction plan. Funding was provided through various sources, including federal and state funds, as well as private donations.

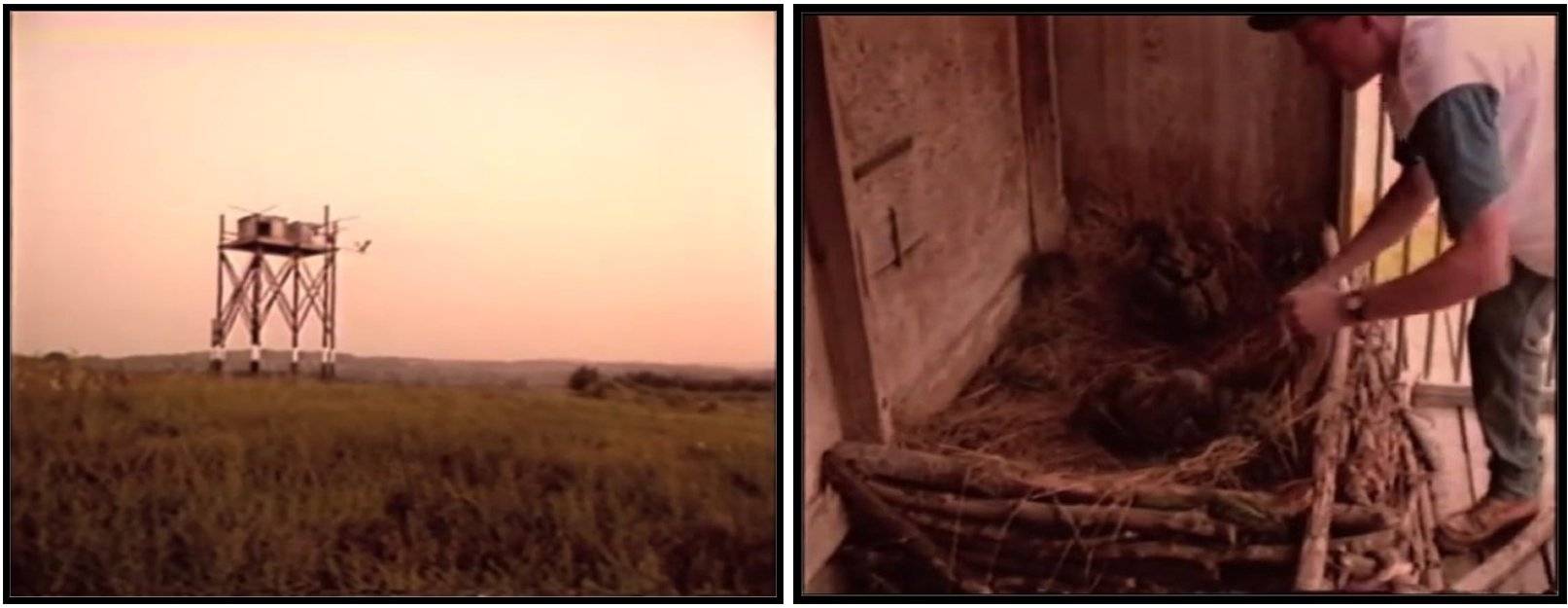

The project officially started in 1983, following extensive planning and preparation. The Pennsylvania Game Commission, with support from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other agencies, identified suitable release sites and built hacking towers. Haldeman Island on the Susquehanna River was selected as one of the primary locations due to its ideal habitat, including abundant food sources and minimal human disturbance.

Bald Eagle Hacking Tower Bald Eagle Hacking Tower |

The first group of young bald eagles was brought to Pennsylvania from Saskatchewan, Canada, in 1983. These eaglets, typically around six weeks old, were placed in artificial nests on the hacking towers. The towers were designed to simulate natural nest sites and were equipped with feeding platforms to provide the young eagles with food while they acclimated to their new environment. The eagles were kept in the towers until they were about 12 weeks old, at which point they were old enough to fledge and begin flying.

Eaglets from Saskatchewan, Canada Eaglets from Saskatchewan, Canada |

Throughout the hacking process, the young eagles were closely monitored by biologists and volunteers. They were fed a diet of fish, similar to what they would eat in the wild, but without human contact to prevent habituation. Once the eagles fledged, they continued to be monitored using radio telemetry to track their movements and ensure their survival in the wild. The initial group of eagles adapted well, and subsequent releases followed over the next few years.

The success of the initial hacking efforts led to continued releases and the expansion of the program. By 1989, more than 88 young bald eagles had been released at various sites across Pennsylvania. These reintroduced eagles began establishing territories and nesting, contributing to a gradual increase in the state’s bald eagle population. The hacking program played a critical role in the recovery of bald eagles in Pennsylvania, transforming the species from a rare sight to a more common presence across the state.

The hacking project laid the foundation for the ongoing conservation and management of bald eagles in Pennsylvania. The state’s bald eagle population has continued to grow, with hundreds of nesting pairs now recorded annually. The successful reintroduction of bald eagles is celebrated as a triumph of wildlife conservation and a testament to the effectiveness of collaborative efforts in restoring endangered species.

Over 300 Nesting Pairs Today!

As of 2023, Pennsylvania is home to over 300 nesting pairs of bald eagles. This number represents a remarkable recovery from the 1980s when only three nesting pairs remained in the state. The success of the reintroduction and conservation efforts, including the hacking program initiated in the early 1980s, has led to a thriving bald eagle population across Pennsylvania. The continued growth of the population is monitored and supported by the Pennsylvania Game Commission and other wildlife organizations, ensuring the ongoing protection and preservation of this iconic species.

Hays Bald Eagle Nest in Pittsburgh, PA Hays Bald Eagle Nest in Pittsburgh, PA |

Eagles nesting in Pittsburgh, PA!

The return of bald eagles to the city of Pittsburgh, PA, is a remarkable example of urban wildlife recovery. Several factors have contributed to this resurgence:

Improved Water Quality

Historically, Pittsburgh’s rivers suffered from severe pollution due to industrial activities, making them unsuitable habitats for bald eagles and other wildlife. Over the past few decades, significant efforts to clean up the rivers and improve water quality have been successful. The Clean Water Act and other environmental regulations have led to reduced pollution, resulting in healthier aquatic ecosystems that support a robust fish population, the primary food source for bald eagles.

Habitat Restoration

Pittsburgh has seen extensive habitat restoration and conservation efforts. Riparian zones along the rivers have been rehabilitated, providing suitable nesting sites and foraging areas for bald eagles. Urban parks and green spaces have also been developed and maintained, creating an environment where wildlife can thrive even in the midst of the city.

Increased Prey Availability

The cleaner rivers and improved habitats have led to an increase in fish populations, which are essential for bald eagles’ diets. Species such as bass, catfish, and carp have rebounded in the rivers around Pittsburgh, providing a reliable food source for the eagles. Additionally, the presence of other wildlife, like waterfowl, adds to the available prey, supporting the eagles’ dietary needs.

Successful Conservation Efforts

The success of broader bald eagle conservation efforts, including the hacking programs and protective regulations, has contributed to the overall recovery of the species. As the population of bald eagles grew in Pennsylvania and surrounding regions, some eagles began to explore and establish new territories, including urban areas like Pittsburgh. The adaptability of bald eagles to urban environments, where they can find ample food and nesting sites, has facilitated their return to the city.

Public Awareness and Support

Public interest and support for bald eagle conservation have played a crucial role in their return to Pittsburgh. Local communities, wildlife organizations, and government agencies have worked together to monitor and protect nesting sites, ensuring that the eagles are not disturbed. Educational programs and outreach efforts have raised awareness about the importance of preserving urban wildlife, fostering a sense of stewardship among residents.

Notable Nesting Sites

One of the most well-known bald eagle nesting sites in Pittsburgh is located in Hays, a neighborhood along the Monongahela River. The Hays bald eagles have become local celebrities, attracting attention from bird watchers and nature enthusiasts. The successful nesting and raising of eaglets in this urban environment highlight the adaptability of bald eagles and the positive impact of conservation efforts.

The combination of improved environmental conditions, habitat restoration, prey availability, and successful conservation programs has created a conducive environment for bald eagles to return to Pittsburgh. Their presence in the city is a testament to the resilience of nature and the effectiveness of collaborative conservation efforts.

Watch Bald Eagles in PixCams

The nesting season for the bald eagles at PixCams has ended this season but there is still action at the three nests we broadcast.

Hays Bald Eagle Nest Camera Hays Bald Eagle Nest Camera |

The Hays Bald Eagle Nest was unsuccessful this nesting season. The nest had a new male, HM2, and they pair laid one egg this season that was not viable.

Watch the Hays nest live here: https://pixcams.com/hays-bald-eagle-nest/

United States Steel Corporation Bald Eagles Nest Camera United States Steel Corporation Bald Eagles Nest Camera |

This season the United States Steel Corporation bald eagles nest fledged one eaglet named Lucky on June 24, 2024 around 7:30 AM

Watch the USS nest live here: https://pixcams.com/u-s-steel-bald-eagle-nest-cam-2-2/

Little Miami Conservancy Bald Eagle Nest Camera Little Miami Conservancy Bald Eagle Nest Camera |

This season the Little Miami Conservancy (LMC) bald eagles nest, located in Miami, Ohio, was highly successful. The LMC nest fledged 3 eaglets! Their fledge dates were June 13, 14, and 20th.

Watch the LMC bald eagle camera live here: https://pixcams.com/lmc-bald-eagle-nest/

Create your own Live Stream!

PixCams has developed live streaming software that is compatible with most inexpensive security type cameras called the EZ Streamer-Pi. The software is free to download and runs on the popular Raspberry Pi single board computer.

The EZ Streamer-Pi was featured by the Raspberry Pi company this month in this Blog post: raspberrypi.com/news/ez-streamer-pi-lets-you-live-stream-from-four-cameras-at-once/

We had a pair of nesting bald eagles from 1998 until two years ago, when hurricanes Matthew, Florence and Isaias proved to be too much for their nest and tree. They still nest not far away, but we would like to establish a new pair in our protected bald eagle habitat. Is there and agency or non-profit we could contact to work with us to establish a nest for an eagle pair?

First off can you tell us where the nest is located so we can tell you what your next steps could be?